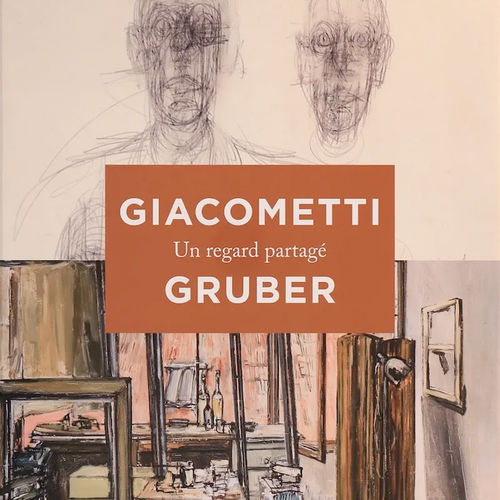

GIACOMETTI – GRUBER un regard partagé: Exhibition

GIACOMETTI – GRUBER, A Shared Perspective

From May 18 to June 30, 2017

Alberto Giacometti and Francis Gruber have known each other since the early 1930s. Their studios were neighbors on Rue Hippolyte-Maindron, not far from the Villa d'Alésia, in the legendary Montparnasse district where artists were renewing aesthetic codes.

The "New Forces" group advocated a "return to order" with priority given to "reality," suspected of academicism, while Fauvism and Cubism had reached an impasse. With the idea of "novelty" regenerated by several figurative factions, including Derain and Fautrier, we witness a dual awakening: the subject is the ultimate path of painting, and reality passes through the human figure, inscribed at the center of a world that foreshadows disaster.

Faced with impending chaos, Surrealism inspired Gruber to create works of extreme singularity. The turbulent fairs and mythological tales evoke the maniera and fantastical naturalism of Jacques Callot's dizzying universe. Giacometti's sculpted stage fictions are of a different order. His inability to represent reality plastically leads him to imagine it in an enigmatic abstraction. When he reconnects with the vision of nature that confirms his break with the Surrealists, he seeks to translate the obviousness of form. He then connects with Balthus, Tal Coat, Tailleux, Hélion, Derain, the pioneer who went against the grain, and Gruber, with whom he becomes more closely associated. The year is 1935.

Giacometti drew daily, visited museums, and explored the erratic models of statuary in Egypt, Byzantium, and proto-Cycladic art.

Behind Gruber's pictorial message, an idealist without illusions, meditative, haunted by the grand technique of an art intelligible to all, vibrates the draughtsman who admired his illustrious elder and fellow Nancy resident, Jacques Callot. These are the origins of Gruber's political commitment. A member of the Front des Artistes de la Résistance, alongside Boris Taslitzky, he was aware of the role of the artist as visual witness. The confusion he unwittingly fell victim to with a painting supposed to be a faithful image of social reality as Fougeron embodied it, is now obsolete. His Homage to Jacques Callot, painted during the Occupation, has the appearance of an explicit danse macabre in its temporal actualization. It is imbued with a strangeness that will experience a surprising diversity during the six years that remain to it, including its magical landscapes in spring, bearers of hope for more cheerful times with the regeneration of nature, sometimes joined by a model.

n both, the recurring theme of the large, static female figure evokes dismay, like an inner reverie that Gruber expresses with Woman Seated on a Green Sofa. The studio, where exterior and interior merge, is imprecisely real in Giacometti, while Gruber precisely describes his manic, disenchanted disorder with the absence of the model and the painter. Laying bare the forms of the world, like human beings, amounts to working to grasp the truth.

Giacometti and Gruber's assiduous practice of drawing strengthened their friendship, which would not weaken, even during the war, when they exchanged correspondence, while Giacometti resided in Switzerland from 1941 to 1945.

For both artists, drawing was a field of continuous experimentation, a laboratory for permanent research. Training at the Grande Chaumière for Giacometti and at the Scandinavian Academy for Gruber paved the way for an ambiguous relationship with the model, already imprisoned in their gaze. For each, nude studies were conducted without complacency or sublimation in order to understand their construction, the orthogonal structures that hold the body upright, seated, and lying down. For Giacometti, Cézanne remained the essential model for his understanding of a living space in which to inscribe the model, whose body remained impossible to circumscribe within its ever-provisional limits.

The studies of Standing Figure and Reclining Nude are found in Gruber's work. Fixed in a frontal pose, the confrontation with the model is immediate in its distancing, leaving all its space for fantasy. Of a striking simplicity, the tormented line gives birth to a nervous writing emphasizing the architectural structure of the figure threatened by the void and the light that passes through it. The profound exploration of reality through drawing is common to them, as for drawing, it is the commentary and the expression of their painted and sculpted work. For the Swiss artist:

"If we mastered drawing, everything else would be possible," he confided to Georges Charbonnier during their interviews (1950-1953).

While copying is not an option, even though they despair of creating a likeness of the model and the pitfall of the vulnerability of the gaze looms, elements of method emerge in the face of the almost desperate question: what is reality? How can it be transcribed without betraying it?

In Gruber's work, the broken contours, described as "Gothic" by Waldemar George, justify his admiration for the masters of the German Renaissance: Aldorfer, Grünewald, Dürer, and also Bosch. For his part, Giacometti develops a rapid and discontinuous network of lines, less to define the form than to make it emerge from a black and white graphic skein of a density obtained by the use of hard pencils where the hatched supports do not exclude the use of the eraser.

Returning to Paris in 1945, Giacometti once again regularly visited Gruber's studio, where he drew Nude in the Studio in relation to the tall figures that, from 1946 onward, had reappeared in Giacometti's studio, particularly Annette.

Standing female figures abounded in a decade that was fertile for both artists, along with portraits and heads for Giacometti. In some nudes, a slight swaying appears, with the body's weight shifting from one foot to the other without threatening balance. In Gruber, the inflected attitude is the expression of a melancholy, an existential languor that permeates all of his work. The woman is mournful, in unison with the universal tragedy from which humanity is barely recovering. She becomes a figure of distress, a "figure of speech" from which Gruber constructs his language. Their shared quest for perfection isolates them in a creation that is always unsatisfied while they return to the loom every day.

Between reality and fantasy, between heritage and imagination, Francis Gruber expresses a "modern" melancholy that dates back to Dürer. It is expressed in a certain immobility, through increasingly tight framing in his interior scenes where his models pose. "The little naked and thin girl in a forest" of which Aragon speaks, yearns to straighten up. Giacometti responds with Walking Man. A similar dismay seems to inhabit them. In the form of a pictorial allegory illuminated by the glazing effects in Gruber's late paintings, he achieves a frozen appearance through the use of siccatives in the composition of pigments, which accentuate the timeless character of his subjects immersed in a cold, luminous field. He is in unison with Giacometti, who explores mixed media with the fury of scraping, facilitating the erosion of masses and the permeability of forms to light.

Giacometti and Gruber both attempt to tame the mystery of the world that remains hidden behind it.

As a final tribute to his accomplice and friend Francis Gruber, Giacometti designs his tombstone in the Thomery cemetery in the Fontainebleau forest.

Lydia Harambourg